Do browsers really hide cookies from other domains?

You’re probably aware of the fact that when you make a request from your front-end to your server, the browser can automatically send along any cookies associated to your server’s domain with that request. You probably also know that you can set CORS headers to bypass the browser’s same-origin policy and let your front-end talk to servers which have a different origin from the front-end.

In addition, you might believe that setting a CORS policy ensures that the browser will not automatically send cookies to your server if the request was coming from an origin not specified in the CORS policy. A malicious website open in another browser tab, for instance (aka a CSRF attack). This, unfortunately, is not entirely true.

“I still am fairly sure that the browser will not send the cookie just because the request is being made to the proper domain. The browser knows the origin the script came from and uses THAT origin to compare with CORS. If I make a website, and the browser is respecting CORS, then there is no way to gain access to cookies from another domain.”

Keeping our users safe as they use our apps is, of course, super important. However, because browsers are highly complex, it can be rather easy to develop an incomplete understanding of the browser security model and make reasoning errors that put our users at risk.

As far as a browser is concerned, “requests” are not all created equal. Are you referring to fetch or XMLHTTPRequest? A regular old form submit with a POST, perhaps? Or just a plain URL link that translates to a GET? What kind of content type does your server accept? Does the endpoint require any data to be sent? The browser behaves slightly differently for each one of these cases, and while correctly setting a CORS policy may protect your users from a subset of them, you can’t be sure that your users will be protected against CSRF until you develop a more holistic understanding of the browser security model.

Hang on, what does CSRF have to do with cookie access from another domain?

I’m going to be talking a lot about ways our apps can be vulnerable to CSRF in this article, so it’s worth clarifying how CSRF relates to cookie access from another domain.

CSRF is an attack that tricks the victim into submitting a malicious request. The “trick” usually involves convincing the victim to land on a malicious domain (the “other” domain that we’ve spoken about) while they are logged in to the target app. Being logged in is a crucial prerequiste of a successful CSRF attack, because this usually means that the browser has a cookie jar for the target app which contains session information (a JWT for example). So, if the malicious domain is somehow able to tell the browser to send along the session cookies with any request the malicious domain makes to the target app, then the target app has no way to tell that the request is malicious or unauthorized. Hence the f-word (“forgery”) in CSRF. If the request being made is state-changing, then you can imagine the amount of damage this might cause.

In other words, a cookie being “accessible”* from another domain is what leads to a CSRF vulnerability, as long as we’re referring to a session cookie. As developers, we want to prevent this from happening. Browsers do some of this work for us, but because browsers are complex, it’s up to us to evaluate tradeoffs, and figure out if we need to do any extra work to keep our users safe.

* A cookie being accessible doesn’t neccesarily mean an attacker can read the contents of the cookie. Just that they can use it to make unauthorized requests

Ok, so do browsers hide cookies from other domains or not?

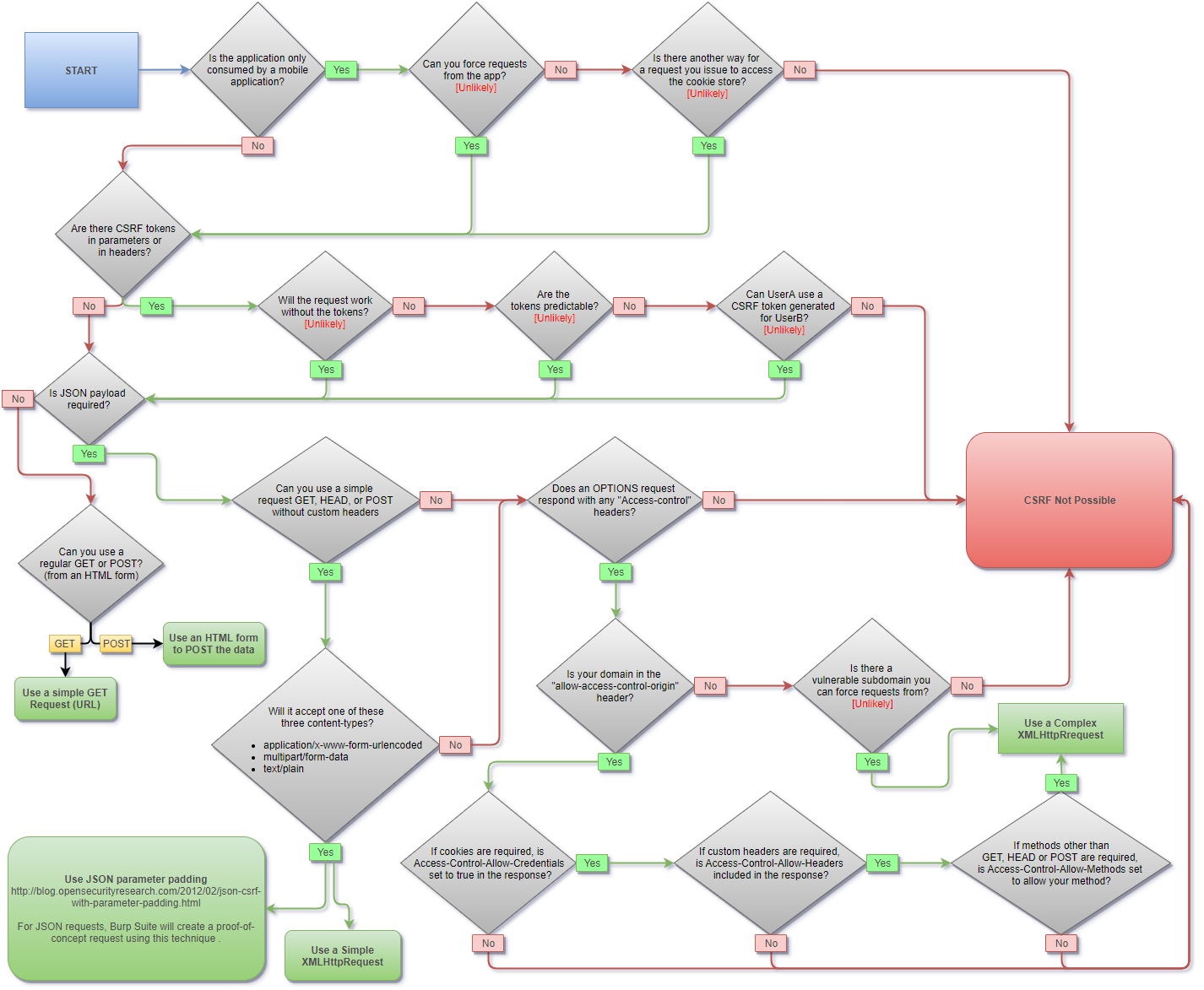

It really depends 😅. Take a look at the flowchart below, developed by Alex Lauerman at Trust Foundry.

- The light green “terminal” boxes (where the flowchart ends) indicate scenarios where CSRF is likely. In these scenarios, an attacker can use the user’s cookies and thus have “access” to them. It’s important to remember that an attacker need not be able to actually read the contents of the cookie or the response to make “trouble”.

- The pathways leading to the red terminal box (the one which says “CSRF not possible”) are worth paying attention to because they tell us how we can prevent CSRF attacks from occuring. In these scenarios, an attacker will not be able to use the user’s cookies to carry out an attack.

- A CORS policy, when set, cannot protect your users from CSRF any more than the same origin policy can. In some cases, when set too permissively, it can potentially increase the likelihood of a CSRF attack.

- The most reliable way to keep CSRF at bay is to use a cryptographically random anti-CSRF token. If you’re using an anti-CSRF token, it almost doesn’t matter if the browser sends cookies to your server or not, because you’d make your server do a little bit of extra work to verify if the cookies can be trusted.

- Though the flowchart doesn’t mention it, correctly setting the

SameSiteflag on your cookies will go a step further to protect your users against CSRF.

CSRF is possible precisely because an attacker is able to use your user’s cookies for their benefit, by exploiting edge cases in the intersection of browser behaviour and the specific security configuration choices you’ve made.

Note: This flowchart, and the associated article, was published in 2014, which means some of the information may be out of date by virtue of browsers having evolved newer security measures. I don’t think this matters for our purposes though.

Is your app vulnerable to CSRF? Use this tool to hack your app and find out!

Here’s a simple tool I wrote to help you develop a more nuanced understanding of browser security. Its primary aim is to get you to explore how concepts like CORS, CSRF, cookie access and others are related.

Instructions

- Choose an app that you want to test for CSRF vulnerabilities.

- Ensure you have running access to your app server logs. You’ll be closely watching logs to verify if the tool is able to make an authenticated request to your app.

- Open the app in another browser tab and log in.

- Once you’re back here, open up devtools and go to the Network tab. We’ll be keeping an eye on this to understand how requests are made.

- Enter in the URL of the endpoint you want to test below (example:

http://localhost:3000/account/12/update). You want to choose an endpoint that requires that the user be logged in. - Select the HTTP Method that your endpoint expects.

- Click ‘Forge Request!’

- Now the important bit: Check your server logs. If you’re vulnerable to CSRF, you will either see a successful authenticated request show up in your logs, or an error that tells you authentication was successful but that a failure occurred later in the request cycle (a data validation error for example).

- If you do see an error that indicates a successful authentication, see if you can go further by modifying the request to include additional data.

- Rinse and repeat! Try forging requests for everything you can get your hands on – toy apps, work apps, local environments, deployed environments, your router’s admin page etc. Basically, anything that can be opened up in a browser. If you can, also try it on different browsers to investigate if there are any differences in behaviour.

How it works

Once you’ve entered in an endpoint and a request method, the tool attempts to:

- Make a simple request via the

fetchAPI to the specified endpoint, using no extra headers and the default content type. - Create a form with

actionandmethodset to the specified endpoint and HTTP method, and submit it using the default content type (the form’s target is set to a hiddeniframeto prevent a redirect).

The idea is that once the tool does this, you’d head over to your server logs and inspect the result of the requests that were made.

Note that in both cases, the tool doesn’t send data to the endpoint. Its only purpose is to see if an authenticated request (matching one of the above two constraints) can be made to your app. Once you verify that this is possible, it should be simple enough to figure out how to send the correct data to it, if needed. The source code for this tool can be found here. Do experiment with sending data, other content types etc.

Disclaimer

This tool is a toy, optimized for learning. While it does serve as a decent starting point to verify if you have a CSRF vulnerability, don't trust it blindly. "Passing" this check doesn't mean you're free from CSRF vulnerabilities. For one, we're restricting ourselves to simple requests. As you saw from the flowchart above, there are potentially ways "complex" requests can be vulnerable to CSRF. Additionally, there are various other things that can go wrong, even if you do everything right (Vulnerabilities in the browser itself, for example. This is rare, but has happened before). That being said, if you find a bug or an issue with this tool, write me!Conclusion

Even though browsers sometimes don’t protect your cookies from being sent across with requests, it’s actually easy to protect your users against CSRF.

While the flowchart we saw earlier looked kind of scary, it turns out that protecting against CSRF is a well known problem that many smart people have thought deeply about. Just two things are needed:

- An anti-CSRF token should be included with every mutating request. Most frameworks have battle-tested solutions for this.

- Your cookies should have the

SameSiteflag set toStrict(orLaxat a minimum).

The main benefit of having these defences in place is that it’ll let you stop worrying about edge cases in browser behaviour as you build and expand your app, because you’re making your server do the work of verifying if a cookie’s origin can be trusted.

If you don’t already know how to add an anti-CSRF token in your framework of choice, do yourself a favour and look it up! If you use Rails, take a look at their security guide. If you use Express, check out the csurf package. I’d also suggest reading the info in both these links regardless of the framework you’re using, because there’s a good bit of useful information in them that is generally applicable!

You might also find my article on mistakes that can be made with JWTs useful.

On the other hand, if all this makes you think you’d rather avoid the hassle of cookies and put your auth tokens in local storage instead, check out my article that goes into why this can actually be less secure.

Finally, if you found this article useful and would like to be notified when I publish a new one, drop your email in the box below.